The "Decline" of Catholicism

Part I: A Diagnosis without Therapy

|

(from "Il 'Declino' del Cattolicesimo: 1a Parte — Una diagnosi senza terapia", Si Si No No, Nov. 15, 2003, pp. 1-4. Translation from Italian by Br. Alexis Bugnolo)

Another Book by Bishop Maggiolini

His Excellency the Most Reverend Alessandro Maggiolini, Bishop of Como, Italy, has taken up once again the subject of the wounds of the Church in a new book entitled, "Catholicism's Decline and Hope" ["Declino e speranza del cattolicesimo" Mondadore, 2003] In his preceeding book, "The End of Our Christianity" ["Fine della nostra cristianità", Piemme, Casale Monferrato, 2001, pp. 239] he considered the possibility of the dissolution of Christendom in Italy and throughout the West, excepting some sort of miracle or radical change. That he has now returned to this argument in a new book signifies that his warning call has not been heard and that the sickness in the Church grows worse; and this absence of reaction is at the same time both the symptom and the cause of the disease.

The symptoms of the decline of Christendom, diagnosed in his first book, are repeated in the second: the crisis of confession, of the family, the lack of conversions, apostasies, the Magisterium's loss of authority, the absence of metaphysics in the formation of the faithful, liturgical disorder, the breakdown of the priesthood, the ambiguity of Episcopal collegiality vis-à-vis the primacy of the Pope, the collapse of certainty in the moral law, etc. "One is face to face with a crisis of the faith and of personal faith," writes His Excellency, "rather than one of moral consistency," a crisis which "disturbs, strikes, and wears out" the Church "from within" (p. 26).

The actual crisis — which we see — is much more perilous after the "pastoral" Council, convoked not to define a dogma, but to care for the diseases of the Church and to reinvigorate Her. It is inevitable that a worldwide process of precipitous, chaotic, unforeseeable and uncontrollable, "modernization", which in many aspects has been as catastrophic as it is active, would have repercussions upon a Church — pastors and flock — that lives in time. Every epoch has constrained the Church to confront the problems of its own time. We, however, point out that, forty years after the close of the Council, the period of transition has ended and that the fruits of the change ought already to be able to be seen; on the contrary, now in the "reformed" Church there is a Bishop who denounces the "decline" of Christendom, addressing himself to the hierarchy that has the responsibility of the Magisterium, explaining the situation in a Church sickened in doctrine and in discipline, a Church that above all must cure Herself.

"Auto-Demolition" from on High

The process of the "auto-demolition" of the Church, was in fact initiated from within, not from without, issued from the center toward the periphery, descended from top to bottom. If there has been a revolution in the Church, it was undertaken with the authority of the Hierarchy. The decline of Catholicism is not the fault of the laity, did not derive from an external assault of enemies, or from a persecution which dispersed the pastors and the flock; on the contrary, perhaps more than ever in the forty years which have followed the Council, the Church eulogized and diplomatically revered by a fully de-christianized world, now satisfied with the changes in the Church.

As an example of this superb rapport between the Church and the world, not to mention the how the world is now lauded in the Church, we cite a significant passage in the Encyclical Redemptor Hominis, from 1979, "§ 17 ... In any case here we cannot not remember with esteem and profound hope for the future, the magnificent effort, accomplished to give life to the United Nations, an effort that tends to define and stabilize the objectives and the inalienable rights of Man, obliging reciprocally the member Nations to a rigorous observance of these. This work has been accepted and ratified by nearly all the Nations of our time, and therefore should constitute a guarantee that the rights of Man become, throughout the whole world, the fundamental principle of action for the good of Man." Of God and of grace non a word; Humanity is to organize itself and can progress even without God!

Yet the reality is otherwise: a hundred years or so ago, the situation of the Church in the world was one of almost complete isolation, but Catholicism appeared united in faith and in obedience to the Magisterium. The mission of the Church was directed principally ad extra. Today the Church is integrated in the world (at least in the West) and makes friends with all, yet is losing Her vigour and urgency, Her unity of faith and doctrine. She deviates from Sacred Tradition, and is losing Her proper identity. Fidelity to the Gospel now needs to be asked of those ad intra.

Salvation without the Church

From the beginning Bishop Maggiolini begins with the problem of the relation between God and man through grace:

"The life of grace coincides with God, who sends His Son to save us, who sends the Spirit from Himself so that He might indwell in an transform the believer. It coincides, then, with the believer himself, who lets himself live — be possessed — by the Spirit, which conforms and unites him to Christ in glory. Grace, therefore, is a relation between God and man, where man is introduced from within to the divine life and shares his being and action through the Lord in the Spirit. This relation acts, in a human person, more like a soul than a guest. And such a presence renders the person himself to the image and likeness of Christ" (p. 22 — cf. St. Ireneus of Lyons, Adversus haereses, PG 7:873, "God became man so that man might become God").

This quote of the Bishop expounds the traditional doctrine taught until yesterday by the Church and it is of the greatest importance for our reflection.

The mystery of grace — we note — is revealed and works only within Christendom and has been ignored and expressly rejected by all other "religions", notwithstanding some of their exterior and illusory appearances. To speak frankly, for the Jews the Law is sufficient and the just man finds in himself the strength to follow the Torah; hence he refuses to follow Christ. As Bishop Maggiolini points out (p. 30),

"Mohammedism had taken its cue — more exterior than anything else — from the Old and New Testament. Let us not equivocate, however, in what sense. The Islamic God is a being that does not look down upon man or the universe with love; its revelation is not accomplished by the Son of God, but is contained in the book of the Koran, written by the Prophet, as if by dictation."

Well said. We might add, however, one correction: Mohammed does not "equivocate; " he takes into consideration Judaism and Christianity to better annihilate them, substituting the Koran for the books of the Old and New Covenant, which he declares have been entirely falsified. Islam knowingly makes a tabula rasa of Divine Revelation and of its history. Jesus in the Koran does not even have a human face.

Considering it impossible, however, to ignore the other religions, which are cropping up among us in the West, and which with a missionary fervour seek out Christians, Bishop Maggiolini gives credence to the necessity of "dialogue" (though the Apostles did not consider it necessary in their pagan world), but warns that syncretism must be avoided:

"Hence the refusal to proclaim Revelation in the fullness of its theoretical and practical dimensions consummates a betrayal not only toward the one who seeks to enter, but also and above all toward Christ who bears us in His arms. And, therefore, how can one pray with other religions? Here we can question ourselves about the pastoral opportunity — and even more importantly upon the dogmatic liceity — of these reunions, above all in a cultural period in which there reigns a certain syncretistic relativism. Certainly, in these each is found praying to his own God for peace. But a question is left out: does it not occur that we ask ourselves if peace be such a value that we consent even to expose to equivocations — practically speaking — the true faith and the fundamental structure of the Church? The necessity for clarity does not seem to enjoy much esteem today, but it is inevitable." (p. 32)

The result is "an anonymous Christian identity" (p. 33): in which "One prefers to be in harmony with all, even when one does not exactly know what that means" (p. 34). It is amazing that one Bishop should need to ask all the Bishops about the necessity for clarity — above all, the successor of St. Peter sitting upon the Apostle's Chair, who — to consider only the past, famous, and most remarkable of his achievements — since the time of the religious encounter at Assisi, recognizes in the sight of the one God the dignity of all the most varied and contradictory forms of human religiosity.

The Crisis of the Magisterium and of Authority

Bishop Maggiolini reaffirms that "The ecclesial Magisterium, then, is a secure point of reference for the understanding of the Bible. For dogma. For the constant and universal teaching. Why not, then, in the catechisms that have been approved by the hierarchy?" (p. 43) This is certainly true, but who is sure that the ecclesial Magisterium is a sure point of reference today, as it was yesterday? It does not seem so, especially when considering what Bishop Maggiolini writes on page 51 of his book:

"Perhaps rather than of the ecclesial Magisterium, it would be more exact, today, to speak of the papal Magisterium. In the actual Church it seems that almost only the Pope speaks. The Bishops, if and when they act, intervene usually as a platoon, with documents of the Episcopal conferences. But always approved beforehand by the Holy See. And justly so. How strange: in the 19th Century the First Vatican Council dogmatised the primacy and infallibility of the Roman Pontiff over the whole Church, and then there intervened the Kettelers, the Mannings . . .. In the last century the Second Vatican Council had proposed in a pastoral manner — but what does that mean? — the sacramentality of the episcopate con the responsibility of teaching and of guiding the college of Bishops with and under the Pope, yet upon the whole Church, and individual bishops seem to have fallen mute: let them dare to utter some devout sermon and behold their Magisterium stops at the confines of the diocese. Why in hell should the affective and effective, collegial spirit prevail in such a manner, before the bishops agree what to say: the time to correct error and to interpret facts has passed, and the texts that have been published are so obscure and monotonous that it would take a notable expertise to comprehend them. And, it is recognized, a robust courage, often, even to read them. And so, that which the ecclesial Magisterium ought to do is delayed . . . and here one speaks of all." (pp. 51-52)

The authority, therefore, of the single Bishop, an authority he has by divine right, which is derived from his apostolic succession, by which in the government of his own diocese the Bishop represents the universal Church, since the time of the council, has been humiliated and annexed by the supremacy of the Episcopal Conference (which is not of divine origin), scaled down by the logic and system of the democratic majority. And only in appearance does the approbation of these deliberations, requested by the Pope, re-establish the monarchic principle of the petrine primacy: for example, in two churches of two German dioceses authorized Rave masses are to be celebrated, unless there arrives a thunderbolt from Rome, that is to say that certainly de facto, if not de iure, Rome no longer has thunderbolts, and the unity of faith and government has perished.

One cannot deny that the Second Vatican Council represents the beginning, and for some the occasion, of the process of the "auto-demolition" of the Church (to quote Pope Paul VI). But everything was not decided at that Council, but everything had its start at that Council. For example, the reform of the Curia, that humbled and rendered innocuous the principle Roman Congregation, the Holy Office, established for the defence of the Faith. The church was voluntarily and thoughtlessly liberated from the weight of Her own spiritual weapons, submitting Herself … to the mystery of the justice of God and to the hope of a miraculous intervention.

The New "Mission" of the Church: "Dialogue"

The Bishop of Como writes:

"in much of contemporary literature, that would call itself Christian, dialogue has in practice taken the place of the proclamation of the faith and of its development . . .. Paul proclaims the conviction, "woe to me if I do not evangelise", that he would betray the mandate he received as an apostle; an even prior to this it would consummate a grave inconsistency in his being as a believer" (p. 57). Our thought for the readers goes first of all to the supreme exponent of dialogue between religions: the Pope. Leaving aside contemporary literature, in the Encyclical Redemptor Hominis there is written: "§ 11. The Second Vatican Council has accomplished an immense work toward the formation of that full and universal understanding of the Church, of which Pope Paul VI wrote in his first Encyclical. Such an understanding — or rather self-understanding of the Church — is formed in "dialogue", which, before it becomes a colloquy, should turn its own attention toward the "the other", that is, towards the one with whom we wish to speak. The Ecumenical Council has given a fundamental impulse toward the formation of the self-understanding of the Church, in a very adequate and competent manner, a vision of the earthly world as a "map" of various religions … The document of the Council dedicated to non-Christian religions is, in particular, full of profound esteem for their great spiritual values, indeed, for the primacy of that which is spiritual and which finds in the life of humanity its own expression in religion, in morality, with repercussions upon his whole culture." (bold-facing not in the original)

Redemptor Hominis is a fundamental Encyclical for the understanding of the concept of John Paul II on the mission of the Church and it is necessary to keep it in mind. The "great spiritual values" which would be found in non-Christian religions would be — according to the Pope — the semina Verbi, which God has sown in all religions and in all cultures, and which hence have the possibility and the duty of dialogue, to be comprehended and joined together in full unity. The fraternal dialogue with all, behold the discovery of the Second Vatican Council! At the end of time, Our Lord Jesus Christ will find a Humanity united and pacified, and He will go to meet it.

According to the Pope, only the "immense work of the Council" would have formed the "full and universal understanding of the Church" . . . "Such an understanding — or rather self-understanding of the Church — is formed in dialogue." The self-understanding of the Church, in a word, is formed only after the Council and in dialogue with the "other" religions, with a small delay, we might add, of nineteen centuries from the Apostolic Age up until 1963 the Church thrived in an imperfect understanding of Truth and of Her own mission in the world, which is, therefore, to say, that the intransigence of St. Paul toward idolatry was an obstacle and a limit on missionary activity! Today, however, the "new" reformed Church has found her place on the "map" of the various religions, the common value of which she has finally come to recognize, after more than nineteen centuries of culpable denial of the common values of the "other" religions, for which the Pope asks pardon on left and right. The Church of Sacred Tradition (Sacred Scriptures, theology, Ecumenical Councils, extraordinary and ordinary Magisterium) had closed Her doors to the world and was imperfect. She needed to update Herself and integrate Herself in the actuality of the world, by discovering dialogue with all and about everything; everything is submitted to discussion and everything is new. The Church had grown old: and e tenebris lux! The Council was the point of departure of a Church that will now travel along the railway of progress. The Church as She was, the Mystical Body of Christ, evidently was not pleasing to many of her unfaithful servants; there is now no attempt to reinvigorate Her; only an attempt to destroy Her venerable divine foundations for the purpose of reconstructing Her upon new human foundations.

Openness to the World: An Optimism Which is as Much Programmed as it is Imbecile

Bishop Maggiolini goes completely against the current when he denounces:

"the equivocation of axioms according to which there is a need to be attentive more to what unites that to what divides" (p. 64); "... the Church has been oriented to inculturate Herself in every context of mentality and comportment. But in this endeavor it is not possible to evaluate a priori in a positive manner every historical contingency that She encounters and in which She immerses Herself. Both because the cultural frames of reference are changing and not always in a positive manner, and because in the history of humanity and of the cosmos there is a certain ambiguity … history is always a place of sin and of evil, … history is also a moment of a dramatic battle on the part of the Christian community" (p. 66; boldfacing not in the original)

From this one concludes — according to us — that the disorderly inculturation in every context of mentality and of comportment provokes theological, doctrinal and moral anarchy, and because the "Culture" of the West, with which the Church believed to have protected Herself, is being defaced; is a culture in crisis and at its death, a culture which serves and accelerates the hedonism of the masses, for which the progresses of science and of technology serve only to makes life in this world better.

Let us return to Bishop Maggiolini:

"It does not require an extraordinary acumen to recognize today that Catholics are in the minority … We have arrived at something like a diaspora: at a dispersion, that is, where each individual believer feels himself strangely alone and struggles to recognize and find another among the masses. They are recognized as exceptions in a society that wanders in every other direction. They are looked upon as strange cases on account of the ideas they profess — if they still find someone to listen — for the rites which they partakes of, for the obedience which they keep for an authority which pretends to command in the Name of God ... Not to speak of a situation of religious pluralism that bears away any tranquillity and which constrains them in constant confrontation and is bristling with difficulty. At least not to enclose himself in a turris eburnea (a tower of ivory) and let the world close in around him. Likewise for the dissolution which awaits him" (pp. 79-80).

There is related here — in this quote — the absolute opposition between Christian life and the ruling, worldly mentality, to which the Church has opened Herself. One has arrived at the point in which it is necessary to remember that the life in this world ends with death, "Who dares still to speak of death?" — writes the Bishop of Como — "... Among other things the liturgy itself seems to want to leap on both feet the discomfort and the torment that She notices — the bite of anguish that strangles Her neck and suffocates Her heart — forcing us to sing "Alleluia", while within in us there is a great desire to rebel with a shout against absurdity and with a plunge into dereliction. The theme of death is forbidden: it sounds of a poor education, of boorishness, of an inhumane upbringing" (p. 80). If a Bishop can speak of this, so can we!

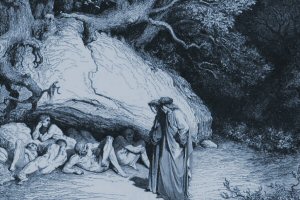

If the thought of death, which after all is a certifiable natural event, has been removed from the conscience of many, imagine what Hell is like: a supernatural reality, a place of devils and of the damned! Bishop Maggiolini reminds us that "the life of each one is being directed toward one's death, to one's judgement and to one's eternal destiny, good or wretched as it may be" (p. 111) and he insists that the infernal punishments are real and consist as much in physical sufferings as in the privation of the beatific vision of God.

It must have been particularly irksome for some to read his remark that:

"the cultural atmosphere that is inhaled by the mentality and comportment that abound today — even by believers within the Church — cloaks itself in a sort of myth of innocence, while all the while the world remains the kingdom of evil: a world which has been overrun by original sin — some of the consequences of which persist even after conversion and baptism — a world which has been profaned by the generations of men which have followed one upon the other, and which by and by ratify and increase that evil, which is termed "the sin of the world"; a world which has been overrun by carelessness and by perversity even in the personal sins of each individual, both among the faithful and the unfaithful, accomplished with repercussions sometimes not even recognizable, but which redound upon history and upon the cosmos. A vision excessively gloomy?" (p. 129)

A vision, in our opinion, which serves in no small measure as an antidote to an optimism which is as much programmed as it is imbecile. Further on the Prelate discusses the "Fuga mundi" and the spiritual battle against the Devil and concupiscence, recalling that "Jesus begins His ministry with the temptation in the desert" (p. 133).

The "Liturgical Reform": A Revolution with Devastating Effects

With his chapter on "The Real Presence" Bishop Maggiolini enters into the heart of the problem. One is not saved alone by himself. The "Fuga mundi" cannot be a flight from a Church emptied of the Real Presence of the Lord. Therefore he asks:

"What is happening in our catholic churches in recent years? A baptistry, ambo, and altar. And Jesus? ... But does Christ render Himself present only after the celebration? One would think so, if one observes the manner in which the particles, not consumed during communion, and the fragments, which remain, are being treated: in a dark corner, protected from indiscrete glances; what is going on? ... Even though, it must be make prominent that Jesus remains among us in Body, Blood, Soul and Divinity: dead and risen and living with a solid, true and concrete presence in an unique manner in the Eucharist. The Eucharist is not always spoken of in terms of the Real Presence of Christ" (p. 140-41).

On the crisis in the priesthood, Bishop Maggiolini says:

"the ideal figure in the Church today is the layman dedicated to his own family and to his own profession. The priest and the consecrated person are not looked to as models of Christian living…" (p. 147); "As much as it concerns more precisely the charism of the priesthood, perhaps the Church today is paying the piper to a certain disinterest for the priestly ministry, while tending to underline in a manner a little one-sided the baptismal priesthood of all the people of God" (p. 148).

We, instead, without mincing words and without respect, would say that the Novus Ordo Missae has been a revolution with devastating effects. In the Catechism of St. Pius X, it was said: "The Holy Mass is the Sacrifice of the Body and Blood of Jesus Christ, under the appearances of the bread and wine, offered to God by the Priest upon the Altar in memory and in renewal of the Sacrifice of the Cross," whereas in the Institutio Novi Messalis Romani of Pope Paul VI it says: "Art. 7 — The Celebration of the Lord or Mass is the holy assembly of reunion of the people of God which is united under the presidency of the priest to celebrate the memorial of the Lord." Here one has passed from the renewal of the Sacrifice of the Lord, which renders it actual and efficacious, to the celebration of a memorial, with the direction of a "presider". In fact, if it were not the renewal of the Sacrifice of the Lord, the one who commemorated it would not be acting in persona Christi and would not exercise a priestly ministry. In place of the Lord, who is the Priest of His own death, there is the people of God reunited in assembly, with a presider, improperly called a priest. It is natural that the assembly consider the Mass an occasion of joy, enlivened frequently by guitars and a choir of youth. If the New Mass can still be considered valid, it is because the words of the consecration of the bread and wine are substantially those of the Lord, although in the Divine Liturgy, the understanding of the expiatory Sacrifice and of the Real Presence has been altered; not at random was the word "Transubstantiation" (of ill-famed Tridentine memory and hence an obstacle to protestants) eliminated from the documents of the Council.

The conclusion is inescapable: either the Council is responsible for the devastation of the Divine Liturgy, turned upside down into an assembly of a protestant sect, or the Council is not responsible: in this second case, the responsibility for the profanation of the Mass rests with Pope Paul VI, who approved the new rite after the Council was concluded. There is no third alternative — Terium non datur.

Why a Diagnosis without Therapy?

Here having arrived face-to-face with the "abomination of desolation", from which there is no human means of salvation, two questions rise up in succession. The first is, "Why?" and the second, "What is to be done?"

Bishop Alessandro Maggiolini has described the symptoms of a fatal illness, but has not traced them back, it seems to us, to their causes; and, if the causes are not singled out, a therapy cannot be prescribed. The Prelate excludes from every responsibility the Second Vatican Council, limiting himself to the observation that there has been a lack of saints after the Council, because "ecumenical councils have not always been decisive" (p. 156). After having described in 156 pages a medical record that does not leave room for hope, the Bishop of Como pulls back and runs out of unsatisfying hypotheses that the Council was not responsible — to lay the blame on the lack of enthusiastic response from all Christians — the hoped for and assured saving effect. In the pre-Conciliar Church, as the same Bishop Maggiolini admits (remembering among others Padre Pio), saints abounded. Holiness, as well as the vocations, both of which are lacking — we might add — are not, hence, the causes. With all respect for the Bishop, who is risking unpopularity to shout out some truths, the point at which he draws back contradicts his entire diagnosis of the symptoms: the sicknesses of the Church are not only those old and recognized to which a remedy could be applied; they are essentially new illnesses, which are struck the Church and the New Missal is the best example of them, because it is the expression of a "new theology". And this is what we propose to demonstrate in the second part of this study.