Shooting the Cardinal

by Steve O'Brien

Film and Betrayal in the Mindszenty Case

(Reprinted with the kind permission of The Latin Mass Magazine.)

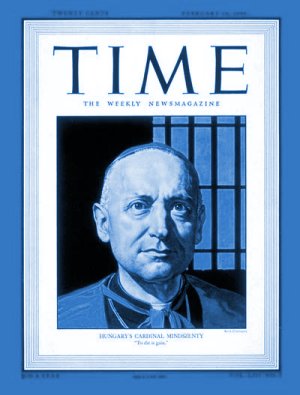

For a moment in the mid-twentieth century the attention of the "Free World" was riveted on the fate of a Roman Catholic prelate, a Hungarian who became a symbol of the divide between East and West. Jozsef Cardinal Mindszenty was an unlikely character to be cast as a champion of the "democracies." Then as now few Americans have the vaguest notion of the complex history of Eastern Europe, much less the Church's place in that history. Also the role of the Church in that area as a partner in governance from the time of King St. Stephen should have been anathema to the enlightened liberal minds of the West.

But the year was 1948 and the foul chickens of World War II were coming home to roost. Franklin Roosevelt lay a'mouldering in his grave while his working partner, whom he called with no apparent irony "good old Uncle Joe," was still firmly ensconced on his bloody throne. Much of the territory that was once the Austro-Hungarian Empire was occupied by Russian troops, and they planned to stay there. During the war the Hungarian governments were collaborationist, with the indigenous pro-Nazi Arrow Cross party carrying out much of the routine atrocity work. There was, however, a national Resistance that up to 1944 had successfully shielded Hungary's Jews from deportation and that viewed Hungary as a bastion of Christian civilization. One of its leaders was Jozsef Mindszenty.

The future cardinal and martyr was born of peasant stock in 1892. He was ordained in 1915 during the war that rent the old empire and at its surcease Hungary fell under the boot of Red dictator Bela Kun, who had Mindszenty jailed. It was the first but not the last time he would be imprisoned by a socialist regime. In the interwar period he chafed under the injustices inflicted on Hungary and was not shocked when the politicians threw in with Germany against the Soviets. As Bishop of Veszprem he continued rescue work for the Jews until these labors again landed him in jail, where he was subjected to the tender mercies of the Gestapo. He remained imprisoned until April 1945, shortly before the end of the war in Europe. Mindszenty emerged a national hero not only to Catholics but to the various Protestant bodies as well. The Jews owed him more than they could ever repay.

Pius XII recognized greatness and rewarded Mindszenty with the Primatial See as Archbishop of Esztergom. Pius and Mindszenty were made of different stuff from the politicians who headed the Western nations. They knew the Reds only too well, and with these two there would be no Yaltas or "gentlemen's agreements." Thirty-one others were installed as cardinals with Mindszenty but when the Pope placed the hat on his head he said, "Among the thirty-two you will be the first to suffer the martyrdom whose symbol this red color is." Both men knew it was a crown of thorns.

For two years the tragedy played out in Hungary. Stalin's promised free elections did occur - the people were free to vote for the Communists or free to stay home. It was apparent to anyone in the world who cared to see that the established regime was a puppet of Moscow. The only barrier to their rule of brutality and moral disorder was the Church, and it therefore had to be destroyed. The government confiscated most of the Church's tillable land, took over the parochial schools, and ejected the teaching orders and replaced them with Marxists. Catholics on the parish level were arrested and tortured for "conspiracy" while the government encouraged a "Peace Priest" movement composed of servile "progressive" collaborators.

At every turn Mindszenty protested the war against the Church. On St. Stephen's Day, December 26, 1948 he was arrested. Prior to being hauled away he declared that he would never sign a confession, and that if one did appear under his signature it would be the result of torture and the shattering of his personality. After a quick show trial in February 1949 Mindszenty was sentenced to life imprisonment.

The Mindszenty farce occurred just as the West was coming to the realization that the Communists were advancing on a11 fronts. The nations of Eastern Europe were satellites of the Soviet Union, Berlin had been cut off and China was soon to fall. Suddenly the fate of one Catholic priest became important to a West long unconcerned about persecution of the Church, a West that had applauded such persecution in Spain only a decade before. The Mindszenty trial put a human face on the moral struggle of one good man against the State.

Hollywood saw the box office potential in this human drama. Though the film industry has from its inception been riddled with Communists and fellow travelers, studio owners knew that "priest" pictures were money makers. Riveting as the Mindszenty story was, however, the major studios balked at filming this tale of terror. Instead, a Poverty Row outfit called Eagle Lion released Guilty of Treason in 1949, not long after the events actually took place. The movie is quite accurate historically, so accurate that even at the time few Americans could have been familiar with the references to such things as Arrow Cross and land redistribution that pepper the film.

The story follows American reporter Tom Kelley as he arrives in Hungary shortly before the Cardinal's arrest. He goes to a cafe that he frequented in the years before the war and finds the patrons a mash of frightened mice and informers. He also meets a music teacher, Stephanie, who is a Hungarian patriot but is also in love with a fanatical Russian colonel. Kelley and Stephanie go to the countryside to seek out the Cardinal and find him at his mother's farm with his dog and shepherd's crook, a simple man of the people who tells them that he much preferred being a village priest.

He explains that the move against the schools is the final move against the Church but that he must continue to preach the Gospel according to Jesus Christ, "not according to Marx and Stalin." Neither Stephanie nor Kelley is Catholic (Kelley? Not Catholic?) but they admire him and plead with him to cut a deal or flee the country. He responds that there can be no agreement between Christ and anti-Christ and proclaims, "I have drawn a line.... I will not surrender the schools to the domination of the State."

Later in the film the domestic politburo has a conference to decide how best to frame Mindszenty, but the man really calling the shots is Soviet Commissar Belov. The group plans to try Mindszenty on a series of trumped-up charges, including anti-Semitism. One member says that the Cardinal had helped the Jews during the war. "Yes," replies another, "but the world outside doesn't know that." They will use the "Big Lie" not merely to kill the man but also to destroy his reputation.

When the Cardinal is finally arrested he leaves behind a note for his mother that echoes the sentiments of the real Mindszenty, stating that if a confession is produced it will be the result of human frailty and he declares it "null and void." The Cardinal is taken to the infamous 60 Andrassy Street, headquarters of the Gestapo during the war and now torture dungeon of the NKVD. He is made to stand in a spotlight in a darkened room while his unseen interrogators accuse him of plotting to restore the monarchy, speculating with American money and working with the Pope to bring the whole world to war with Russia. He collapses without confessing and after weeks of this the Red suits are at their wits' end. One of them admits that "when a strong man has no feelings of guilt he may never confess." In desperation they decide to use the hypnotic drug scopolamine to reduce his mind to putty.

Mindszenty's trial actually takes up only a few moments of the film, which scarcely matters since everyone in the audience already knew the sentence of life imprisonment meted out in the real world. In the last scene of the film Kelley is back home addressing his colleagues in the Overseas Press Club. He tells them, "If you want peace with the Russian bear, brother, take it from me ...you can't let him walk all over you."

Guilty of Treason is an extraordinary time capsule from the start of the Cold War. The film's message that the Communists were out to destroy not only high churchmen but also music teachers and Budapest waiters was clearly understood, and with the West losing ground on the four points of the globe it was realistically terrifying. The same year that Guilty of 'Treason was released American intelligence learned that the Soviets had exploded an atomic bomb. A few months later, Korea. As captivating as the Mindszenty story was, the new threat of atomic war between the superpowers made the fate of one courageous prelate and millions of captives behind the Iron Curtain seem insignificant.

For the next six years the flesh-and-blood Cardinal languished in a succession of moldy and freezing cells, subject to the blows and blasphemies of psychotic guards. On the outside, the Hungarian government completed the total subjugation of the Church. Religious orders were thrown out of their buildings and jailed. Nuns were prohibited from nursing as they had been from teaching. Mindszenty's ostensible successor as head of the hierarchy was Archbishop Joseph Grosz, who acquiesced in every government demand. His craven behavior earned him a Mindszenty-style arrest and trial. Unlike Mindszenty, Grosz confessed to every charge that the government could cook up, though breaking this rotten twig did not compensate for the Reds' limited success with the Cardinal.

By 1955 the "Free World" had moved onto other crises but the drama of the Mindszenty story still had plenty of mileage, and that year a film was produced entitled The Prisoner, starring Alec Guinness. The Prisoner is a very different film from Guilty of Treason. The politics of Eastern Europe and the tensions between East and West are not mentioned, nor is the Cardinal ever named. There is no attempt to make the location appear to be Hungary and the entire production, from the actors' accents to the sets, is as English as soccer hooligans. Despite this, the main character is most definitely Mindszenty. The circumstances of his arrest, the references to his leadership role in the Resistance, and the mental torture during questioning all replicate Mindszenty's ordeal.

The film opens with the Cardinal's arrest after Mass. Like the character in Guilty of Treason and the real Mindszenty, the Cardinal makes a statement to the effect that any reported confession would be a lie or the "result of human weakness." The Cardinal's Inquisitor is said to be from a noble house and is also a lawyer and doctor. He was part of the anti-Nazi Resistance and tells the Cardinal that he was a hero but now he is a national monument that must be destroyed. The Cardinal promises the Inquisitor that breaking him will not be easy because he is proud - proud of his record with the Inquisitor's predecessors, the Gestapo. It's the opening salvo in the intellectual battle between them; the rest of the movie rides on the sharp repartee between the two. At their next meeting the Inquisitor warns the Cardinal that he will get at the truth. The Cardinal replies, "Surely it's a confession you're after, not the truth." The Inquisitor admits that "they," meaning the State, really want his mind. Now the Cardinal is afraid.

The Cardinal is worn down by incessant questioning, illustrated by his change into prison garb and shots of him tramping up and down the prison stairs. As in Mindszenty's cell, the Cardinal's light cannot be turned off and he is deprived of sleep. At another session the Inquisitor makes some progress when the Cardinal admits that as a boy he always stank because of his work at a fish market and that he was ashamed of his mother, who was a waterfront prostitute (definitely not historically accurate). Like Lady Macbeth, the future Cardinal scrubbed and scrubbed to erase the filth and the guilt but succeeded only in eradicating his fingerprints.

The Inquisitor finally wears away his resistance and persuades him that his confessing to being a traitor will wipe the slate clean. At the trial the Inquisitor acts as prosecutor and gets the Cardinal to admit to everything under the sun, to the shock of the foreign press. Despite his professional triumph, the Inquisitor is sickened with himself. He tells his flunky that the Cardinal's problem was really an excess of humility. "A proud man would have been more skeptical."

Though the Cardinal has been sentenced to death, the Inquisitor himself brings him the news that the sentence has been commuted and he is free to go. The Cardinal is not overjoyed at this news because without the respect of the people the rest of his life will be a living hell. The Inquisitor, in an un-Communist gesture of mercy, pulls a pistol and offers to shoot the Cardinal as he would a wounded animal. The Cardinal refuses this gesture too because it would make the Inquisitor a murderer. This is the last straw. The Inquisitor, totally defeated, admits: "Then the laugh is on me. You go out from under my hands as a stronger man than when you came to me." As the Cardinal leaves the prison the Inquisitor watches him through a barred window. It is he who is trapped and he knows that he will now be devoured by his own system.

The Prisoner, as it happened, was wrapped too soon because Mindszenty's story, which had seemed to be fini, had scarcely begun. By 1956 Stalin was dead and Khrushchev was making some unusual noises. In October the Hungarians rose in revolt. Mindszenty had no clue of what was happening on the street; his guards told him that the rabble outside the prison was shouting for his blood. A few days later he was released and indeed a mob of locals set upon him. But instead of ripping his flesh they grabbed at the liberated hero to kiss his clothes. When he returned to Budapest the deposed Reds quivered over this ghost who would not stay buried, but in a radio broadcast he counseled against revenge. The Soviets were not so forgiving, and tanks rumbled to crush this unpleasant incident. A marked man, Mindszenty sought asylum in the American embassy as his last resort. Now a second long Purgatory had begun. Pius spoke out repeatedly against this latest example of Soviet terror but the West, heedless of its own liberation rhetoric, was deaf.

When The Prisoner was released, the Church was still the implacable foe of communism. Frail Pius stood as a Colossus against both right and left totalitarianism. When Pius departed this world there ensued a moral void in the Vatican that has never been filled. By the early 1960s both the Western governments and the Novus Ordo popes decided that accommodation with the Communists was preferable to the archaic notions of Pius and Mindszenty. John XXIII and successor Paul VI welcomed a breath of fresh air into the Church, and that odor included cooperation with the Reds. The new Ostpolitik, managed by Paul's Secretary of State Agostino Casaroli, hadn't room for Christian warriors of Mindszenty's stamp. The position of the Hungarian government was strengthened when Casaroli entered negotiations with the appalling regime of Janos Kadar. As the Cold War thawed, the freeze was put on Mindszenty. The American government made it understood that he was no longer welcome at the embassy. Worse still, Paul sent a functionary to persuade Mindszenty to leave, but only after signing a document full of stipulations that favored the Reds and essentially blaming himself for his ordeal. The confession that the Communists could not torture out of him was being forced on him by the Pope!

Driven from his native land against his wishes, Mindszenty celebrated Mass in Rome with Paul on October 23, 1971. The Pope told him, "You are and remain archbishop of Esztergom and primate of Hungary." It was the Judas kiss. For two years Mindszenty traveled, a living testament to truth, a man who had been scourged, humiliated, imprisoned and finally banished for the Church's sake. In the fall of 1973, as he prepared to publish his Memoirs, revealing the entire story to the world, he suffered the final betrayal. Paul, fearful that the truth would upset the new spirit of coexistence with the Marxists, "asked" Mindszenty to resign his office. When Mindszenty refused, Paul declared his See vacant, handing the Communists a smashing victory.

If Mindszenty's story is that of the rise and fall of the West's resistance to communism it is also the chronicle of Catholicism's self-emasculation. In the 1950s a man such as Mindszenty could be portrayed as a hero of Western culture even though both American and English history is rife with hatred toward the Church. When the political mood changed to one of coexistence and detente rather than containment, Mindszenty became an albatross to the appeasers and so the Pilates of government were desperate to wash their hands of him. Still, politicians are not expected to act on principle, and therefore the Church's role in Mindszenty's agony is far more damning.

Since movies, for good or ill, have a pervasive influence on American culture, perhaps a serious film that told Mindszenty's whole story could have some effect on the somnolent Catholics in the West. Guilty of Treason and The Prisoner are artifacts of their day. An updated film that follows the prelate through his embassy exile and his pathetic end would be a heart-wrenching drama. But knowing what we know now, the Communists, despicable as they are, would no longer be the primary villains.

Steve O'Brien holds a Ph.D. in history from Boston College and is the author of Blackrobe in Blue: The Naval Chaplaincy of John O. Foley, S.J., 1942-46.