Faith and Fiction

by Matthew M. Anger

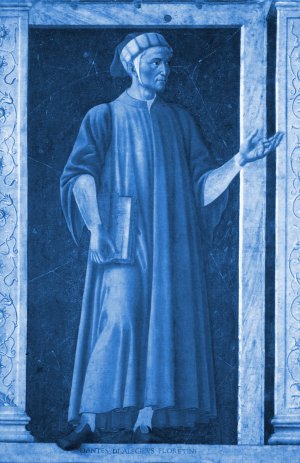

Andrea del Castagno, 'Famous Persons: Dante Allighieri' (c. 1450)

Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence |

The Moral Responsibility of the Catholic Novelist

In his best-selling novel, The Disciple (1889), French Catholic writer Paul Bourget tells the story of philosopher Adrien Sixte, who lives a quiet, unassuming life in Paris. Yet the professor's works — advocating materialism and positivism — wield a terrible influence over an admiring but unstable student whose actions, in turn, lead to the tragic death of a young woman.

The point of Bourget's book, frankly admitted, is that every writer is accountable for what he writes. "No man of letters, however insignificant he may be," he says in the preface, "but should tremble at the responsibility.... May you find here a proof that the friend who writes these lines has the merit, if he possesses no other, of believing profoundly in the seriousness of his art." Unfortunately, few novelists make the moral analysis of their writings as easy as Bourget.

Truth or Pleasure?

Generally, any attempt to address aesthetical works on a moral level is placed at an immediate disadvantage. The charge of philistinism hangs in the air. But immoral content in art cannot glibly dismissed in the name of mere urbanity. Plato grappled with this very issue over 2,000 years ago. Speaking in The Laws of the edifying qualities of music (which included dramatic works, the precursor of modern fiction) he denied that it could be pleasure for its own sake.

This is not to overlook the sheer enjoyment that good art provides. "So far I agree," says Plato, "with the many that the excellence of music is to be measured by pleasure." But he adds

[T]he pleasure must be that of the good and educated, or better still, of one supremely virtuous and educated man. The true judge must have both wisdom and courage. For he must lead the multitude and not be led by them, and must not weakly yield to the uproar of the theatre, nor give false judgment out of that mouth which has just appealed to the Gods.

More recently, Rev. Patrick F. Norris, O. P. has commented that the immediate and intuitive impact of the arts can have a tremendous influence for either good or ill. "Although our emotions and experience can be valid sources of moral reflection, they must be in critical correlation with reason and the Gospel." The danger is that insincere artists can play on emotions in such as a way as to "authenticate" immoral choices.

[B]ecause the arts subtly persuade the mind by moving the emotions, the effect on the moral compasses of people we encounter in [ordinary situations] can sometimes be more profound than the didactic nature of the classroom.... Drama can move the emotions and the person toward the truth; it can also manipulate the emotions and sunder the person from the truth" (Homiletic & Pastoral Review, December 2000).

The Catholic Novelist's Vocation

When dealing with the morality of novelists who claim to be Catholic one must first ask how they approach their trade. Aesthetically, there is the manner of dealing with characters, plot and ideas within the analogous form of the novel. The novelist believes that truth expressed as a fictional metaphor is often more powerful that a direct statement. For that very reason any concern raised over morality in fiction is a testament to the potential power of the writer's craft which surpasses that of many other fields for the sheer universality and accessibility of the medium.

Some champions of the modern fictional format explain that novels cannot be heavy-handed, "faith-promoting" tracts, but must be alive and necessarily ambiguous and multifaceted. But here we run up against other, potentially dangerous ambiguities that have plagued Catholics (writers and readers alike) for the last few decades.

Novel writing is described by contemporary practitioners as a "vocation." More than that, being intuitive and like a great piece of poetry, it has been referred to as a "form of prayer." Granted there is truth in this, but until we know an author's underlying premises we can never tell where these generalizations will take us. Is he raising the mundane to a higher level by ennobling it? Or is it a case of diluting religious meaning to the insipid level of titillating but noncommittal depictions?

Maritain on Artistic Responsibility

Catholic philosopher Jacques Maritain tackled the ambiguities and nuances of this dilemma in The Responsibility of the Artist (1960). In this work he says that the key to the problem lies in the fact that art and morality tend to operate in separate and seemingly autonomous realms. There is a level in which art, like the work of any skilled craftsman or technician, operates independently of ethical considerations. "A man may be a great artist and be bad man." The failure to acknowledge this fact can lead to errors on the part of the agnostic and the moralist alike. But this differentiation does not imply a complete disconnect.

Man is composed of body and soul. In this life the two are distinct, yet inseparable. Operating from a Thomistic perspective, Maritain explains that

From the point of view of Art, the artist is responsible only to his work. From the point of view of Morality, to assume that "it doesn't not matter what one writes" is permissible only to the insane; the artist is responsible to the good of human life, in himself and in his fellow men.

Maritain further insists on the point that "because an artist is a man before being an artist, the autonomous world of morality is simply superior to (and more inclusive than) the autonomous world of art." There are still those agnostic aesthetes who insist on art's complete independence. Maritain replies that this fallacy is born of "a confusion between Art taken in itself and separately, which exists only in our mind, and Art as it really exists, that is, as a virtue of man.... The motto Art for Art's sake simply disregards the world of morality, and the values and rights of human life."

Maturity versus Obscenity

While the famous French novelist Georges Bernanos did not like "preachy" writers, he was equally offended by authors who claimed to be Catholic but whose writings betrayed sin and despair. He was a harsh critic of the controversial works of Francois Mauriac. For him, Mauriac was "the tortured author of so many books in which despair of the flesh sweats on every page, like muddy water from the walls of a cellar." Needless to say, the moral climate of fiction writing has not generally improved since Bernanos' day.

Contemporary Catholic novelists serve as a convenient benchmark of how writers of professed faith engage the current culture. Unfortunately, we see concessions on the part of writers — not only the openly liberal Andrew Greeley school of fiction, but even the more conservative — who have taken graphic depictions of sex and violence as the norm. The result is an illogical and irresponsible disconnect between theology and ethics which results in a kind of "split personality" on the part of Christians.

The morally laxist explanation is that it is not possible to glamorize vice in fiction, because our conscience knows better. It's like cheap booze that leaves a bad aftertaste. But this is a glib way of dodging the question. According to this view, there should not be any alcoholics in the world either, since everyone knows that excessive drinking is bad for you. Oscar Wilde was more honest about man's concupiscence when he said: "The public has an insatiable curiosity to know everything, except what is worth knowing. Journalism, conscious of this, and having tradesman — like habits, supplies their demands."

Like the exhibitionistic novels of Anne Rice, the difference between high brow smut and the literary contents of Playboy is one of degree rather than kind. To defer to Church's teachings on the matter

Pornography consists in removing real or simulated sexual acts from the intimacy of the partners, in order to display them deliberately to third parties. It offends against chastity because it perverts the conjugal act.... It immerses all who are involved in the illusion of a fantasy world. It is a grave offense (CCC, 2354).

Labeling sexually explicit novels as "pornographic" may seem harsh, but only because of the moral insensitivity which society has acquired in recent decades.

The method of the irresponsible artist cannot be hidden behind euphemisms or aesthetic window dressing. "Both the gross hard-core pornography trafficked in films, magazines, and pervasively on the Internet and the soft-core pornography that pervades the media, especially advertising, cheapen and distort human beauty and sexuality" (Rev. John Joseph Myers, A Theological Reflection on the Human Body, 2002).

This is by no means a denigration of those "mature themes" which are often an inseparable part of good creative writing. Catholic novelists are not restricted to the sort of unsophisticated fiction penned decades ago by Canon Sheehan or Msgr. Owen Francis Dudley. Indeed, authors like Evelyn Waugh or Flannery O'Connor were able to push the envelope as far as they could without breaking it. But the point at which we transition from factual discussions of adultery to details of lascivious activities, we are in the realm of voyeurism. Indeed, the recent obsession with — and philosophical justification of — shameless curiosity reveals a dysfunction that is far worse than the old time burlesque or risqué comedy.

Flannery O'Connor and Moral Limits

The problem most people have today with morality in the arts is one of definition. But for Flannery O'Connor, the measure was intuitive: "Obscenity is obscenity." Sadly, since her time, there has been tremendous equivocation on this point. Rather than let the Church set the moral criterion, many practicing Catholics have followed the world's standard — which is, quite simply, to have no standard at all. Hence the precipitous decline into bestial levels of vice.

As Flannery O'Connor explains, the Catholic artist can only address mature themes when his (or her) approach is both religiously and morally mature. "Do not make the absurd attempt," she says, "to sever in yourself the artist and the Christian. They are one, if you really are a Christian." It is this very fixity on metaphysical grounds that allows one greater freedom aesthetically without being hampered by false, worldly standards.

Christian dogma is about the only thing left in the world that surely guards and respects mystery. The fiction writer is an observer, first, last, and always, but he cannot be an adequate observer unless he is free from uncertainty about what he sees. Those who have no absolute values cannot let the relative remain relative; they are always raising it to the level of the absolute.

O'Connor added:

The Catholic fiction writer is entirely free to observe. He feels no call to take on the duties of God to create a new universe. He feels perfectly free to look at the one we already have and to show exactly what he sees. He feels no need to apologize for the ways of God to man or to avoid looking at the ways of man to God. For him, to "tidy up reality" is certainly to succumb to the sin of pride. Open and free observation is founded on our ultimate faith that the universe is meaningful, as the Church teaches.

Readers may recall that Fyodor Dostoyevsky takes the same frank approach in his novel The Brothers Karamazov. But in his case, as in the stories of O'Connor, this candor operates neither randomly nor gratuitously. It concerns itself with realism about moral and physical deformity, not graphic vulgarity. In a New York Times interview in 1955, O'Connor dealt with the matter bluntly. The error of obscenity, even in art, is that "it draws attention to itself and away from the plan of the work." By contrast, an example of what she would call "a reasonable use of the unreasonable" is her brilliant short story, "The Partridge Festival." Few works of literature have more candidly conveyed the unglamorous nature of obscenity without actually resorting to it.

To what extent a modern author can speak to his readers colloquially without "dumbing down" his intellect or his morals is something that deserves further treatment elsewhere. It may be that the trend towards verisimilitude, or "realism," of the last century was justified. But the approach of a writer like Flannery O'Connor lies in the realm of opinion not ethics. One is free to agree or disagree with her style, which is a subjective question. Meanwhile, she was wise enough to practice restraint in things that were objective.

As Maritain put it, "There are no precepts in natural law or in the Decalogue dealing with painting and poetry, prescribing a particular style or forbidding another." Understanding the distinction between art and morals certainly explains why it is possible for a devout reader to appreciate the artistic merit of agnostic or even anti-Christian writers like H. G. Wells, Victor Hugo or Jack London. Yet it is also true that the reason we can enjoy them — while distancing ourselves from their false philosophies — is that these men wrote at a time when moral restraints were still generally in place. There was not that flagrant sensuality which completely vitiates a work, such as O'Connor warned against.

Living Vicariously

The modern novelist may speak of the desire to "live through one's characters." But is it true to say that we are "mature enough" to keep a distance between characters' private sexual details and our own private moral realm? The incautious writer overlooks a simple point. The glamour of vice exists because in our fallen state we tend to irrationally choose lesser goods over greater ones. The restraints of reason will diminish as we focus on the immediate acts of vice, in themselves attractive, while permitting the awareness of the long-term consequences of those acts to fade in the background. The idea that morality is pure and unspoiled reason, free from the gravitational effects of Original Sin, is a well-known point of view — but it is not Christian. The kind of detachment in the midst of vice only comes with spiritual maturity which, in turn, is the product of virtuous habits and avoiding obvious sources of sin. Otherwise, the man who seeks out temptations is half way to giving into them.

The writer of offensive fiction may not be guilty of overt nihilism. Rather, the real problem seems to be a question of confusing means and ends. Moral theology tells us that we never employ vice in the pursuit of good. In this instance, the "means" — producing "popular" and "profitable" novels — will completely undermine the supposed ends — a story with a God-centered perspective. There is the additional danger that such casual artistry on the part of a self-professed Catholic sows greater confusion than openly pornographic mainstream literature, which makes no claim to Christian inspiration. It gives readers a false sense of security, as if there were "sin free" methods of vicariously engaging in vicious behavior.

The Relativity Argument

The only defense left for ethical evasion is cultural relativism. The usual canard is trotted out, that "these things are out there" and we can't just ignore them. It is a matter of "honesty." But therein lies the utilitarian implication that morality itself is a sort of pious falsehood. Jacques Maritain was uncompromising on this point

It is also possible, and probable, that the moral conscience of an artist whose work is really pernicious is contaminated by questionable human inclinations, warped instincts, or resentments or vices, which he shelters behind his art: then he will claim... that his work is innocent and incapable of offending morality, and is even the greatest tribute ever paid to virtue. But this is not a solution, it is a fake, or an escape.

Many people seem to have taken the moral shift for granted, as if it were inevitable. This includes those faithful whom one suspects are victims of bad catechesis rather than willful malevolence. Yet everything is traceable back to human will and moral choices. One only has to consider the successful, if short-lived, history of the Catholic Church's campaign against immorality in films in the first half of the last century which positively shaped ethical standards for millions, including non-Catholics.

Conclusion

Literature separated from morality not only suffers from irresponsibility and defect, but is also a powerful tool in the hands of the unscrupulous. What is offered as harmless entertainment in bad novels or prurient TV sit-coms can end up as a clever and amusing way of "normalizing" practices still regarded by most of the population as distasteful. Such misuse of popular media is partly a reflection of a sinking culture, but is also evidence of how people can promote a particular ideology by indirect means.

Nevertheless, if the growing backlash against immorality in film and fashion is any indication, moral standards in literature are possible. Authors, of course, dislike any thought of bowdlerizing their works, but if we wish to avoid external censorship, we must practice self-censorship. In this regard, actor Jim Caviezel provides a good example of an artist realizing his vocation, rather than offering the sanctimonious platitudes that our culture (including American Catholicism) abounds in. In the 2002 film, High Crimes, Mr. Caviziel refused to film a "love scene" with his on-screen wife Ashley Judd because possible nudity conflicted with his Catholic faith. Other artists should take note.

In the past, writers had much of their restraint imposed on them (even if unconsciously and indirectly). But the minute standards are relaxed people tend to exert their concupiscence to the utmost limit. It is only the continual pressure of morality and a lived faith that will overcome these temptations or at least keep them in check. The Church is not blind to subjective situations and the changes in society's mores and expectations. It will always shape its responses in accord with the dictates of prudence and charity. But the objective standards remain unchanged.

As Catholic scholar Christopher Dawson said, "The recovery of moral control and the return of spiritual order have now become the indispensable conditions of human survival."

Matthew Anger is a freelance journalist who has written essays on history, philosophy and literature from a Catholic perspective. He lives with his wife and seven children in the Richmond, Virginia area, where he is employed as a web/multimedia designer. In addition to Seattle Catholic, he contributes to The Latin Mass and Homiletic & Pastoral Review.