Culture Wars Over "The Passion"

by Matthew M. Anger

|

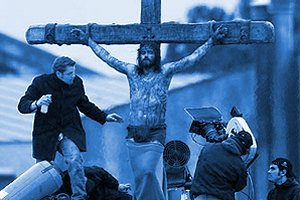

The Impact of Gibson's Film on Protestants, Jews and Catholics

Professing a faith as blunt and unvarnished as his film portrayal of Christ, Mel Gibson has discomfited and challenged his peers. In his ABC interview, the actor/director said that Christ "was beaten for our iniquities. He was wounded for our transgressions. And by his wounds we are healed. That's the point of the film." But Diane Sawyer, and others like her, didn't get the point—which is not surprising, since celebrity expressions of "Christianity" tend to take the form of noncommittal religious statements, like Britney Spears testifying that she believes in the "sanctity of marriage" despite her 55-hour Las Vegas wedding and annulment.

These things are a reminder that media talk about religion is not the same as talking religion. And that, coming from one of Hollywood's leading men, is exactly what has taken the secular establishment by surprise. The stale Peter Jennings-style exegesis of the entertainment world is no longer grabbing headlines. Instead, a multi-million dollar production of Christ's final hours from an orthodox perspective has become an unforeseen change agent throughout the nominally Christian West.

The Passion has already shed new light on our society's practice (or neglect) of religion. It has even brought forth unanticipated alliances amidst the all too expected controversy. One could call it a surprise sequel to the lost Culture Wars of the 1990s. The ideological legions of "political correctness" are massing again for what they expect to be an easy triumph, yet it is clear that something is different. What is happening now is quite unlike the political retreats of the past. The players are after higher stakes.

What the film will mean for the American Church is a story that is still unfolding. But The Passion has some surprising implications for our faith, and particularly our relations with Protestants and Jews. Only now are those implications becoming apparent.

Protestants: From Crosses to Nails

Crucifixion nail pendants are now the best-selling item in Evangelical Christian stores. Linked as merchandise to The Passion, they have attained a new symbolism that is perhaps lost even on its biggest customers. Charles Houser, of the American Bible Society explains that "The cross has become such a benign jewelry item . . . The shock of its original form . . . is lost to modern people…. Choosing the detail of the spike would be to reinvigorate the image. They're really trying to capture that this was that day's form of execution."

It is a remarkable admission that brings Protestants full circle. Consider that for centuries a hallmark of Protestantism was its effective iconoclasm against the mystery of the Crucifixion. The Corpus of Christ was removed, leaving a barren cross, which has since become a ubiquitous item of agnostic jewelry. Gone was the penitential symbolism of the redemptive suffering of the Messiah.

Crucifixion nails in Bible stores are just one of the items evincing pre-Reformation piety. Similar phenomena are visible in fundamentalist Protestantism, like inspirational works which discuss the "Blood of Christ" (The Life-Changing Power in the Blood of Christ, The Precious Blood of Christ, Written in Blood, etc.) It is reminiscent, however vaguely, of the centuries-old Catholic devotion to the Sacred Blood.

Seventy years ago, Hilaire Belloc argued that traditional Protestantism was a decaying holdover of an earlier conflict, doomed to give way to more potent forces. In a sense this prediction still holds true. Insofar as a vigorous Protestantism has survived in the United States (it is moribund in Europe), it has broken in many respects with old-style Calvinism.

A side effect of this break is revealed in the significant number of Evangelicals, many of them prominent former ministers, who have converted in recent decades—documented in the Surprised by Truth books by Patrick Madrid. Putting aside the rather pointless "inclusiveness" that neo-orthodox Catholics extend toward Protestantism, it is an undeniably positive development. We must credit the good will of converts, who are attracted by the resiliency of basic Catholic truth, rather than interfaith dialogues.

Meanwhile, the phenomenon of The Passion is compelling for conservative Protestants even if they can't entirely understand why it would focus on "just the last twelve hours of the life of the Messiah." But at least they feel bound to see it, just as many liberal and nominal Catholics will find reasons to avoid it. What exactly they will get out of it is hard to tell.

If it is merely an "affirmation" of the emotional creed some are used to, the impact will be intense but fleeting. To speak of a movie as religious experience is a mistake. There is no turnkey, ready-made "justification" or short cut to salvation. But the message of The Passion may go deeper with some, if they ponder it.

The redemptive drama of Our Lord, as Gibson presents it, is novel and striking to Protestants. One wonders if they will envy our familiarity with it. We pray the Sorrowful Mysteries of the Rosary, we reenact the suffering of Our Lord during Holy Week, and perform the Stations of the Cross (the original, pre-movie version of The Passion). These practices, especially as they are revived and promoted, are a strong draw to the non-Catholic who craves tangible evidence of his faith in a personal God—the sort of evidence that people raised on frugal forms of worship are starving for.

Jews: New Divisions, New Alliances

The attacks on Gibson's film have been virulent and hypocritical. Speaking of the specifically anti-Catholic bias of the establishment, Richard Roeper of the Chicago Sun-Times said "no other religious group gets bashed with such frequency." At the head of the media posse is Abraham Foxman of the Anti-Defamation League (ADL).

Nevertheless, if we get past the annoyance of Foxman's increasingly feeble attempts to slander Gibson, the most obvious point from the discussions leading up to the movie's release is that The Passion isn't about anti-Semitism—though some people would like it to be about that. It is ultimately about those who mock religion and those who respect it. Nor have Jews been uniformly pleased with the self-serving scare tactics of some of their co-religionists. Conservatives have been particularly upset, demonstrating that Judaism is hardly a monolithic bloc (despite what some Jews and non-Jews would have us believe).

In contrast to American pressure groups, the Executive Council of Australian Jewry has given The Passion its thumbs up. David Klinghoffer, writing in the Los Angeles Times challenged Gibson's critics and even defended the historicity of the Gospel account of the Crucifixion, based on Talmudic sources.

Jewish movie critic Michael Medved, who is regularly featured on Catholic Exchange, also came out in defense of The Passion. "Indignant denunciations of a movie," said Medved, "that its critics haven't even seen, coming nearly a year before that picture's scheduled release, suggest an agenda beyond honest evaluation of the film's aesthetic or theological substance."

The best rebuttal of anti-Gibson commentators is that of Orthodox Jewish Rabbi Daniel Lapin, featured on Lew Rockwell:

Those Jewish organizations that have squandered both time and money futilely protesting Passion, ostensibly in order to prevent pogroms in Pittsburgh, can hardly be proud of their performance.... From audiences around America, I am encountering bitterness at Jewish organizations insisting that belief in the New Testament is de facto evidence of anti-Semitism. Christians heard Jewish leaders denouncing Gibson for making a movie that follows Gospel accounts of the Crucifixion long before any of them had even seen the movie.

Long-held assumptions about Jewish and Catholic relations are being challenged in a way that opens up possibilities for traditionalists—possibilities that ecumenists and liberals instinctively would overlook. Michael Medved, in a very broad way, sums up the mood when he notes the change in attitude of American Jews towards Christians since September 11th. "This troubles liberal activists, who worry over the ever-increasing influence of religious traditionalism in American life. The ADL, for instance, has been outspokenly critical of the so-called Christian right" for more than twenty years.

Admittedly there are more nuances than Medved admits of. Yet the real question is not one of special interests and foreign policy, on which point there is plenty of room for disagreement, but the deeper religious issues.

The Jewish people are sui generis (unique), and the West's relation with Judaism defies the simplistic explanations given by secular sources, both left and right. Yet one also cannot place much confidence in the chimerical "Ecumenical Jihad" of neo-conservatives like Peter Kreeft. There are other, more legitimate, instances of collaboration between Jews and the Church, especially in the days before Nazism and the Holocaust set the tone for debate on the subject. In particular, the Pontificate of St. Pius X is a model of what Jewish-Catholic relations can be like.

St. Pius X was a champion of the old triumphalist faith. Yet he also encouraged good relations with Jews, told Italian Catholics to vote for conservative Jewish candidates against leftist politicians, acknowledged the contributions of Jews toward Catholic charities and orphanages, and even condemned anti-Semitic pogroms in Russia and the scurrilous tales of Jewish "ritual sacrifice" of Christian children.

It was this "pre-Conciliar" Catholicism (which Mel Gibson has personally embraced) that brought many prominent Jews to the faith. The Rastisbonne brothers, Ven. Francis Libermann, Paul Loewengard, Karl Stern, and Rabbi Zolli of Rome are just a few of those who found their way into the Church without the aid of Nostrae Aetate or embarrassing Vatican apologies to other religions.

Catholics: The Decisive Factor

The Passion has been accurately described as more an event than a movie. Gibson's production is indeed a catalyst, tapping into desires and frustrations not unlike those transforming works of literature and art in the past. A film cannot take the place of personal growth in faith and piety. Nevertheless more than one convert has been influenced by features of Catholic culture (like the cathedrals of Europe or the great works of the Church philosophers). While the film probably won't elicit "mass conversions," it may change the minds of many.

As for the effect on the Catholic world, the overwhelmingly positive Evangelical reception given to Mel Gibson's film is important. The Passion has demonstrated that the sacramental faith that the Modernists at the Council sought to replace is one of the things that is truly attractive to non-Catholics.

It is also heartening to see the stubborn response of some members of the hierarchy. Perhaps the wearying calls for self-denunciation have finally hit a nerve. At any rate, when the contentious Foxman met with U.S. Archbishop John P. Foley at the Vatican, the latter declared he had no intention of issuing a statement about Gibson's movie. Foley followed the unambiguous line of Papal spokesman Joaquin Navarro-Valls: "I had absolutely no thought regarding any responsibility on the part of the Jews. I took it as a meditation on the Passion of Jesus, and my own responsibility and the responsibility of all of us for the suffering and death of Jesus."

The secularists, be they Diane Sawyer or Abraham Foxman, have trod on a hornets' nest, and for once, the media upset is a pleasure to watch. What is different this time around is that long humiliated Christians have found themselves with no more room for retreat. After all, attacks on a personal God are rather personal. And the fact that the steamroller of secularism has stalled for even a moment will embolden the opposition.

The defiance of Christians, however, goes beyond the question of Gospel inerrancy. Serious Protestants have taken strong positions on moral issues as well, though in each and every case it is clear that Catholicism must lead the way. Even the most low-Church Christians will testify with palpable envy that only Rome is truly decisive on things like abortion. As for Gibson's vision of the death of the Savior, it is admittedly a personal one, but one that is clearly colored by Catholic theology. The fact that so many are embracing its pre-modernist depiction of Christ is, one hopes, a further sign that the days of soft-Catholicism are numbered.

Above all, the key to The Passion is the thing which Msgr. Ronald Knox talked about in his famous spiritual retreats: "The Love of the Lord—I don't mean God's Love of us; I mean our love for Him—is a frightening subject. The whole business you and I have in the world, the whole point of our being in the world at all is to love God." In a nutshell, the Culture Wars are born of this "fright." There are those who acknowledge it and those who deny it. Mel Gibson's movie has made that very clear.

Matthew Anger is a freelance Catholic journalist who writes on historical and literary subjects. He lives with his wife and seven children in the Richmond, Virginia area.