by Patrick J. Gallo

|

Dachau lies 15 km northwest of Munich, just a short car or train ride. To visit Dachau today is to awaken the ghosts of a terrible past. Hundreds of tourists visit Dachau each day with their own reasons for doing so. Dachau in its present state is an approximation of the reality of 70 years ago. While one can get a sense of the physical layout of the camp, it's impossible to recreate in one's imagination the suffering that took place within.

The concentration camp was established in March of 1933 at a site where a munitions factory once stood. Theodor Eicke was appointed commandant of the camp. Dachau was intended for political prisoners. The first group to be interned included Social Democrats, Communists, and homosexuals who were guarded by the SS. Later, political dissidents and other "undesirables" from occupied countries were interned there. After the Kristallnacht pogrom about 10,000 Jews from all of Germany were sent to the camp. Official records show that 225,000 persons passed through Dachau and about 50,000 died.

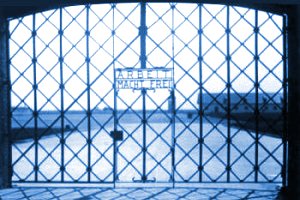

Today, the same ominous slogan stands above the entrance as it did nearly 70 years ago: Arbeit macht frei (work makes one free). There are five major memorials, one to the unknown prisoner and the others to the Protestant, Russian Orthodox, Jewish, and Catholic victims of Nazi brutality. The latter is a simple stone building with a tall metal tower, a bell hanging inside, and a large gold cross on top. Inside is a small altar with a wreath of blood-red roses, a crucifix above it and a row of prayer candles. Dachau had the largest group of Catholic clergy inmates than any other camp. Who were they? Why were they there?

The Nazi persecution of the churches was a combination of "political nihilism and ideological fanaticism." They set out to destroy the existing social order and were fanatically determined to create a pure Aryan super race. According to John Conway, "The Nazis' antagonism towards the Churches arose from their intolerance of any compromise with a system of belief that spanned the centuries and embraced all men under a doctrine of equality before God. ... The Nazi radicals were motivated not only by a desire for total control, but an ideological fanaticism that believed it possible to create an ersatz religion of blood and soil." Their mission was to create a secular substitute for Christianity.

Hitler expressed his hatred of the Catholic Church in private dinner conversations. On one occasion he remarked to his dinner guests, "I hate the Jews because they have given that man, Jesus, to the world," and on another, "Bolshevism is Christianity's illegitimate child. Both are inventions of the Jew." Hitler and the Nazi hierarchy were obsessed with the Christian churches. The Catholic Church was especially hated and feared. The recent release of heretofore classified OSS intercepts of Nazi communications reveals the depth of that hatred and fear.

We have had for some time the records of the private and public comments of Hitler, Bormann, Goebbels, Heydrich, Himmler and the other racial fanatics. Martin Bormann's, Circular on the Relationship of National Socialism and Christianity, makes it clear, "National Socialism and Christianity are irreconcilable," and links Christianity with Jewry. Josef Goebbels' diary entries are replete with similar references to Christianity, "He (Hitler) views Christianity as a symptom of decay. Rightly so. It is a branch of the Jewish race ...in the end they will be destroyed..." Goebbels recorded in 1942, "The Pope (Pius XII) has made a Christmas speech. Full of bitter, covert attacks against the Reich and National Socialism. All of the forces of internationalism are against us. We must break them." Heydrich reacted to that same speech stating, "Here he is clearly speaking on behalf of the Jews."

With Hitler's approval, Reinhard Heydrich issued a directive ordering the suppression of certain "secret" and religious societies. He also ordered the internment in concentration camps of all individuals connected with those organizations. The Gestapo proceeded to compile a list of sects that were prohibited by the regime. At the top of the list was the Catholic Church. An officer of the SD described Heydrich's hatred of the Church, "It was almost pathological in its intensity and sometimes caused this otherwise cold and calculating schemer to lose all sense of proportion and logic." Heydrich had considered "political Catholicism" the most dangerous threat to the Nazi regime, and he insisted that the destruction of the Church should take precedence over actions against Communists, Jews and Freemasons. He was prepared to authorize the most extreme measures to ensure the destruction of this dangerous enemy.

Wasn't it the Vatican that opposed their euthanasia program? Didn't Cardinal Pacelli (Pius XII) register numerous protests with regard to the regime's violations of the Concordat? Didn't Cardinal Pacelli have a major hand in drafting Pius XI's encyclical, Mit Brennender Sorge, that unequivocally denounced the Nazi regime? The encyclical was to be read on Palm Sunday in every Church in Germany. This outraged and angered the Nazis, who tried to confiscate every copy they could get their hands on. Goebbels reacted "furiously and full of wrath" to this "provocation." He then noted that Hitler wanted to "strike against the Vatican," since the clerics "did not understand patience and mildness," and now they should "find out how stern, tough, and merciless we can be."

Just before the Papal enclave that elevated Cardinal Pacelli to the papacy, Das Reich in a preemptive attack wrote, "Pius XI was half Jew, for his mother was a Dutch Jewess; but Cardinal Pacelli is a full Jew." Nor did they forget Pius XII's first encyclical, and The New York Times on October 28, 1939 that proclaimed in its headline, "Pope Condemns Dictators, Treaty Violators, Racism: Urges Restoring Poland," It went on to report, "It is Germany that stands condemned above any country or any movement in this encyclical — the Germany of Hitler and National Socialism." The Nazis forbade the publication and distribution of the encyclical. The Allies subsequently dropped 88,000 copies over Germany.

Wasn't Pius XII the head of a so-called neutral state, really pro-Allies and secretly aiding them? Hitler detected the Pope's hand in helping to oust Mussolini. Professor Richard Breitman who has been granted access to recently declassified OSS intercepts of Nazi cables has said, "Hitler distrusted the Holy See because it hid Jews." How did they know this? Breitman states, "They had spies in the Vatican." Breitman was impressed by the deep Nazi hostility toward Pius XII. Why not strike directly at the Vatican? In 1943 Hitler directed SS General Karl Wolff to develop a plan to enter the Vatican and seize documents, Pius XII and other Vatican officials.

On July 21, 1935 Victor Klemperer recorded in his diary, "The struggle against Catholics, 'enemies of the state,' both reactionary and Communist, is increasing." Klemperer's published diaries I Shall Bear Witness, provide a day-by-day account of the interior of Nazi Germany and a compelling chronicle of the evolving persecution of Germany's Jews, Catholics and Protestants. In January 1938 he wrote, "...anti-Semitism has again been very much in the foreground ( it rotates: now the Jews, now the Catholics, now the Protestant ministers)." The next month Klemperer noted, "Priests imprisoned, priests expelled from the pulpit..."

According to the best estimate some 2,771 clergyman were inmates in Dachau. The largest number of clergyman were Catholic priests, seminarians, and lay brothers. A disproportionate number were the 1,780 Polish clergy, 780 of whom died in Dachau. Three thousand additional Polish priests were sent to other concentration camps. In addition, 780 priests died at Mauthausen, 300 at Sachsenhausen and 5,000 in Buchenwald. With the Nazi conquest of Western Europe, hundreds of priests were shot or shipped to concentration camps, many dying en route. Also many nuns were either imprisoned or shot.

Giovanni Palatucci, a deeply religious young police officer, helped to save an estimated 5,000 Jewish refugees by destroying index files, and securing false identity papers. He arranged for their transportation to southern Italy where his uncles Giuseppe Palatucci, the Bishop of Compagna, and Alfonso Palatucci, the Provincial of the Franciscan Order in Puglia, had established safe havens. He was arrested by the Nazis and sent to Dachau. On February 10, 1945, ten weeks before the liberation of Dachau, the deeply religious 36 year old died. Fritz Michael Gerlich director of the Catholic newspaper Der Gerade Weg (The Narrow Way) was arrested and sent to Dachau, where he died. Henry Zwans, a Jesuit secondary school teacher in The Hague, was arrested for distributing copies of Bishop von Galen's homilies and died there. Leo DeConnick instructed the Belgian clergy to resist the Nazis. He was arrested and imprisoned in Dachau.

Parish priests were sent to Dachau for quoting or reading Pius XI's encyclical Mit Brennender Sorge or for providing false identity papers to Jews or POW's. Father Bernhard Lichtenberg, Provost of St.Hednig's Cathedral in Berlin, became known for his evening prayers for the fallen soldiers on both sides, Jews and all the persecuted. Lichtenberg said prayers in public for the Jews on the evening of Kristallnacht. He called on all Catholics to protect Jews and asked to be deported with Jews to the Ghetto of Lodz. Lichtenberg was arrested by the Gestapo and imprisoned for two years. He died of heart failure while being transported to Dachau.

Dachau was a cruel parody of the Nazi totalitarian state that sent them there. All possible measures were taken to dehumanize the inmates and make them live in perpetual fear and anxiety. On arrival, all prisoners were stripped naked and their hair shaved. They were outfitted in ill-fitting prison uniforms, striped jacket and pants, cap and wooden clogs. To further dehumanize the prisoners they no longer had names, but were known by a number. One such inmate was Karl Leisner, a German seminarian, who became No. 22356.

By 1940, all Catholic clergy in Dachau were placed in three main barracks built for 360 people. Every morning came roll call, and then work within or outside the camp began. In bitter winter, some were given the task of removing the snow off the roofs without shovels. The prisoners' diet was calculated to produce constant hunger. In the morning there was a mug of black coffee and a slice of bread. In the afternoon a small cup of watery soup, and at night margarine and a piece of black bread. It didn't take long for an inmate to be reduced to a skeleton. After a day of hard labor and malnourishment, the inmates trudged back to the filthy, vermin-infested barracks. There was the constant fear of becoming sick and having to go to the contagious wards of the infirmary. The SS guards refused to enter. Priests volunteered to minister to the sick.

Priests were not immune to beatings, starvation or medical experimentation. From the very moment they entered the camp, prisoners were beaten by the SS guards who tried to break their spirit by physical violence. Father Andreas Rieser, who seemed unbroken, was singled out by one guard and beaten repeatedly. The guard then forced the priest to fashion a crown from a piece of barbed wire, a sick representation of Christ's crown of thorns. Beatings were frequent and took place without rhyme or reason. In one portion of the camp stood a crematorium that was used to dispose of those who died in the camp.

A few priests committed suicide by throwing themselves onto to the electrified fence that surrounded the camp. Some priests despaired or just gave up, but most clung tenaciously to their faith. What the Nazis could not do was break their faith in God. They either prayed in private or held clandestine group prayer meetings. They set up a secret makeshift chapel in the corner of one of the barracks. All priests tried to help ease the suffering of their fellow inmates

One of the most remarkable episodes to come out of Dachau is the story of Karl Leisner. Leisner was admitted to the seminary in 1934 by Bishop von Galen, who was an uncompromising opponent of the Nazis. In 1934, Leisner's studies in the seminary were interrupted when he was called up for compulsory work service. All of the workers while in service were subjected to Nazi propaganda and bitter attacks on the Catholic Church. The Gestapo considered Leisner to be dangerous because he organized Sunday Mass for the other conscripts. His home was raided by the Gestapo and his papers, correspondence, and diaries were confiscated.

After Leisner's compulsory service was completed he returned to the seminary. Following a failed attempt to assassinate Hitler in 1939, Leisner commented that it was a pity that Hitler had escaped. The Gestapo had a file on him and took him into custody. During the interrogation, Leisner did not back away from his statement.

In December of 1940, Leisner was sent to Dachau. The 25 year-old seminarian tried to keep up the morale of his fellow inmates and helped others to survive every way possible. But it didn't take long for his tuberculosis, which had been in remission, to become active again. One evening, two SS guards came into his barracks for inspection, picked him out of the group and beat him unconscious. In March of 1942, he began spitting blood and was admitted to the dreaded hospital block, where he was placed in a room with 150 other TB patients.

Four months after the invasion of Normandy, Bishop Gabriel Piquet of Clermont-Ferrand was sent to Dachau for providing false identity papers. While he was there, someone suggested that he might ordain Karl Leisner. One priest made contact with a woman who bicycled in and out of the camp. She agreed to take letters to Bishop von Galen and Archbishop Faulhaber that sought their authorization for the ordination. Eventually, an affirmative message came back. The necessary vestments and materials were obtained through a secret network or they were crudely fashioned.

On December 17, 1944, in a moving and secret ceremony, Karl Leisner was ordained to the priesthood. Due to his weakened condition, he celebrated his first Mass in secret, nine days after his ordination. Leisner survived Dachau after its liberation, but the tuberculosis that ravaged his health was in its terminal stage. Karl Leisner died in Cleves on August 12, 1945. Many priests died shortly after they were liberated from Dachau and the other concentration camps — a direct result of the maltreatment and the illnesses that developed while they were interned.

Patrick J. Gallo is the author of For Love and Country: The Italian Resistance and Enemies: Mussolini and the Antifascists. He is an Adjunct Professor of Political Science at New York University.