Pius XII: From World War to Culture War

by Matthew M. Anger

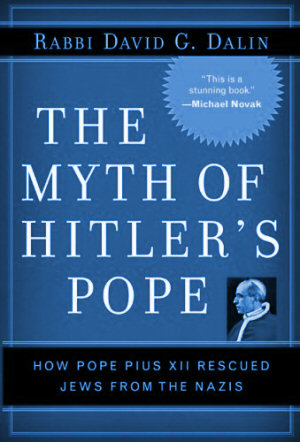

A Review of Rabbi Dalin's "The Myth of Hitler's Pope"

"Very few of the many recent books about Pius XII and the Holocaust are actually about Pius XII and the Holocaust," says Rabbi David G. Dalin. In this bitingly perceptive phrase, Dalin sums up the main thrust of The Myth of Hitler's Pope: How Pius XII Rescued Jews from the Nazis, just released by Regnery Press.

Considering its far-reaching scope, Rabbi Dalin's book is an amazingly compact study. He has distilled a vast amount of research by other authors, whom he gratefully acknowledges (especially the works of Pinchas Lapide and Ronald Rychlak), concentrating on a few key and memorable points. But it is more than a summary. The author has also contributed some new findings and highlighted points hitherto overlooked. For that reason alone, the book is an ideal briefing on the subject. There is the added advantage that it is written by a prominent Jewish intellectual. The Myth of Hitler's Pope cannot be "written off as merely minority Catholic pleading."

The Reason Why

Despite the misleading nature of the controversy — one which Dalin questions from the outset — the first critics of the wartime papacy were not Jews. Among the worst attacks were those of leftist non-Jews, such as Carlo Falconi (author of The Silence of Pius XII), not to mention German liberal Rolf Hochhuth, whose 1963 play, The Deputy, set the tone for subsequent derogatory media portrayals of wartime Catholicism. By contrast, says Dalin, Pope Pius XII "was widely praised [during his lifetime] for having saved hundreds of thousands of Jewish lives during the Holocaust." He provides an impressive list of Jews who testified on the pope's behalf, including Albert Einstein, Golda Meir and Chaim Weizmann. Dalin believes that to "deny and delegitimize their collective memory and experience of the Holocaust," as some have done, "is to engage in a subtle yet profound form of Holocaust denial."

The most obvious source of the black legend about the papacy emanated from Communist Russia, a point noted by the author. There were others with an axe to grind. As revealed in a recent issue of Sandro Magister's Chiesa, liberal French Catholic Emmanuel Mounier began implicating Pius XII in "racist" politics as early as 1939. Subsequent detractors have made the same charge, working (presumably) from the same bias.

While the immediate accusations against Pius XII lie at the heart of Dalin's book, he takes his analysis a step further. The vilification of the pope can only be understood in terms of a political agenda — the "liberal culture war against tradition." In that respect, the controversy is a "microcosm" of a much greater conflict, albeit an extremely important one. While this aspect has been addressed previously, the fact that it is recognized by a non-Catholic makes it more striking:

The liberal bestselling attacks on the pope and the Catholic Church are really an intra-Catholic argument about the direction of the Church today. The Holocaust is simply the biggest club available for liberal Catholics to use against traditional Catholics in their attempt to bash the papacy and thereby to smash traditional Catholic teaching — especially on issues relating to sexuality, including abortion, contraception, celibacy, and the role of women in the Church. The anti-papal polemics of ex-seminarians like Garry Wills and John Cornwell (author of Hitler's Pope), of ex-priests like James Carroll, and of other lapsed or angry liberal Catholics exploit the tragedy of the Jewish people during the Holocaust to foster their own political agenda of forcing changes on the Catholic Church today.

Case Dismissed

If John Cornwell's contentious screed is at all typical (and it most undoubtedly is), then the attacks on Pius XII quickly collapse into a mass of innuendo and crude prevarication. The most damning evidence that Cornwell could come up with, to "prove" that the future pope, Eugenio Pacelli, was pro-Nazi and anti-Semitic is a poor translation of a letter. The letter was written while Pacelli was Papal Nuncio in Munich in 1919. As cited in Hitler's Pope, the correspondence gives the impression that he viewed all Jews as a vile Communist "rabble." But given a correct rendering of the Italian, which Dalin provides, the accusation evaporates like early morning dew in the full light of the sun. It turns out that Pacelli's communication is a factual account of Communist activities in Bavaria after World War I, which in no way betrays anti-Semitic bigotry. Such drivel would hardly be worth commenting on, especially since Cornwell offers a retraction in his latest, and equally silly, book about John Paul II (The Pontiff in Winter). But, as one might expect, his "about-face received only slight notice in the liberal media."

If anything belies the notion that Pacelli was sympathetic towards German racial nationalists it is his friendship with Bruno Walter, the Jewish conductor of the Munich Opera. The two men met upon Pacelli's arrival in Munich in 1917, and Walter would later convert to Catholicism. Says Dalin:

Incredibly, the Pacelli-Walter friendship is never mentioned by Pope Pius XII's critics — or even by his defenders, who have missed this significant portion of Pacelli's life. But in Walter's memoir, Theme and Variations, Walter reveals how Pacelli helped free his wrongly imprisoned Jewish friend and fellow musician Ossip Gabrilowtisch during an anti-Semitic pogrom in Bavaria.

Such consistent opposition to anti-Semitism was typical of Pacelli's career, as secretary of state, under Pius XI, and finally as Pope Pius XII. Dalin discusses this, including his role in opposing the direction of Nazi policies in the 1930s.

As for the harrowing years of World War II, The Myth of Hitler's Pope provides a formidable list of actions undertaken by Pius XII, which demonstrate a sustained and coordinated effort on behalf of persecuted Jews. Of them all perhaps the most illustrative is his effort to halt the Nazi sweep of October 1943. Dalin presents a decisive refutation of Susan Zucotti's claims (Under His Very Windows) that the pope fiddled while Rome's Jews were carted off to the gas chambers. When dealing with such charges, Dalin operates on different lines than his opponents. He prefers to rely on eye-witness testimony. Dalin recalls the words of Michael Tagliacozzo, an Italian Jewish survivor of the Rome deportations now living in Israel:

Tagliocozzo says that Pius XII's actions were decisive in rescuing 80 percent of Roman Jewry. He dismisses the notion... that the pope was not behind the rescue effort. "There was much confusion in those days, but all knew that the pope and the Church would have helped us. After the Nazis' action, the pontiff, who had already ordered the opening of convents, schools, and churches to rescue the persecuted, opened cloistered convents to allow the persecuted to hide...."

If all else fails, leftists fall back to their last ditch claim. The massive rescue effort (which saved over 800,000 Jewish lives, by Israeli diplomat Pinchas Lapide's estimation) was somehow orchestrated without the pope's knowledge or even against his wishes. It is about on the same level as suggestions that the Final Solution was implemented behind Hitler's back. As Dalin notes, many Catholics have been acclaimed as "righteous gentiles" by the Yad Vashem Holocaust Museum in Israel. Among them Tibor Baranski, Bishop Giuseppi Palatucci, Fr. Pierre-Marie Benoit and Msgr. Angelo Rotta. Without exception, they cited the pope's express directives and assistance as paramount in their rescue work. Not surprisingly, it is the author's firm belief that "Catholic and Jewish leaders and scholars should... continue to work together to support and promote the cause of recognizing and honoring Pius XII as a 'righteous gentile.'"

Jews and the Papacy

With most of the reviewer focus on the Holocaust, a particularly interesting facet of The Myth of Hitler's Pope is apt to be overlooked. It is the question of Catholic-Jewish relations in the centuries leading up to World War II. Fascinating in its own right, this thorny topic is key to anti-Catholic contentions that the Holocaust is the logical outcome of a morally bankrupt Church. James Carroll's Constantine's Sword (2002), for example, maintains that anti-Semitism is central to Christianity, and to Catholic theology in particular. But whether dealing with shallow pseudo-research like this or pop theological condemnations of the Gospels, Dalin is quick to defend what he sees as Christianity's essentially positive nature.

The historical fact is that popes have often spoken out in defense of the Jews, have protected them during times of persecution and pogroms, and have protected their right to worship freely in their synagogues. Popes have traditionally defended Jews from wild anti-Semitic allegations. Popes regularly condemned anti-Semites who sought to incite violence against Jews. Popes employed Jewish physicians in the Vatican and counted Jews among their personal confidants and friends. You won't find these facts in the liberal attack books, but they are true.

The author draws on Jewish and non-Catholic scholars, as well as important primary documents. As an aside, it is worth noting that most of the examples of papal charity towards Jews cited by Dalin took place well before Vatican II. Church leaders clearly were capable of asserting doctrinal rectitude, and engaging in controversy on a religious level, without resorting to un-Christian hatred or violence against innocent non-Catholics.

Dalin cites the decree of Gregory I (590-605) Sicut Judaeis which affirms that Jews "should have no infringement of their rights.... We forbid to vilify the Jews." Such pronouncements became, if anything, more frequent in the Middle Ages with increasing tensions between Jewish and Christian communities. The "blood libel" was one of the most persistent and outrageous claims leveled against Jews, and one repeatedly denounced by popes (beginning with Pope Innocent IV in 1247). Unscrupulous demagogues claimed that Jews were ritually murdering Christians, particularly children, and using their blood in the unleavened bread at the Passover meal. The last instance of a pope refuting such violent rumors was when St. Pius X intervened on behalf of the Russian Jew, Mendel Beilis, who was placed on trial in 1913 for "ritual murder," a patently absurd charge lacking in evidence. Under Vatican pressure, Tsar Nicholas had him acquitted. Nor was this the first time the sainted Pontiff assisted Jews. Eight years earlier he responded to anti-Jewish pogroms by sending clear instructions to Catholic bishops in the Russian Empire to oppose such violence.

Hitler's Mufti

Rabbi Dalin sees plenty of incongruity in the current "moral outrage" against Catholicism. With all the negative press about Christianity, it is not the modern West that presents the world with the most entrenched forms of anti-Semitism. "The liberal papal critics who have been so quick to condemn the alleged anti-Semitism of Pius XII and John Paul II have been much slower to condemn the very real and well-documented anti-Semitic violence" perpetrated by Islamic fundamentalists. Meanwhile, the Muslim Arab media has even "resurrected the blood libel" and "routinely charged Jews with committing ritual sacrifice."

In this light, the real villain of The Myth of Hitler's Pope is Hajj Amin al-Husseini, the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem during World War II. Recognized as the imam of his day, al-Husseini exerted a crucial influence on radical Arab-Muslim political thought. He was, among other things, the chief mentor of terrorist leader Yasser Arafat.

Today, sixty years after the Holocaust, the wartime career and historical significance of Hitler's mufti, Hajj Amin al-Husseini, should be better remembered and understood. The "most dangerous" cleric in modern history, to use John Cornwell's phrase, was not Pope Pius XII but Hajj Amin al-Husseini, whose anti-Jewish Islamic fundamentalism was as dangerous in World War II as it is today. While in Berlin, al-Husseini met privately with Hitler on numerous occasions, and called publicly — and repeatedly — for the destruction of European Jewry. The grand mufti was the Nazi collaborator par excellence. "Hitler's mufti" is truth. "Hitler's pope" is myth.

Like Nazism or Marxism, contemporary Islamic radicalism represents a pseudo-messianic escapist creed that promises paradise through the bloody extermination of one's enemies. Dalin has an easy job of demonstrating the affinity of extremist Muslims for Nazism, even well after Germany's defeat. In recent years Mein Kampf has become an Arabic bestseller (reprinted in 2001 by Arafat's Palestinian Authority). It is a reminder that throughout history, be it the Middle Ages or today, anti-Semitism has been employed by radical and unscrupulous individuals, often religious heretics, exploiting the passions of the mob. As such it has been consistently condemned by the Church — a fact noted in many other works, including those of Hilaire Belloc.

"Other Bonds"

In his interview with Zionist leader Theodore Herzl in 1904, St. Pius X expressed his belief that "there are other bonds than those of religion: courtesy and philanthropy. These we do not deny to the Jews." It may be more than coincidental that the past few years have seen a growing collaboration of Jews and Catholics in the face of common threats. The most obvious is the Islamic terror already noted. But there are other challenges as well, particularly the aggressive measures of leftist secularists. Again papal history repeats itself, since St. Pius X urged the collaboration of Italian Catholic and conservative Jewish leaders in the face of anti-clerical policies in the early 20th century.

In 2001 Rabbi Dalin went to bat for Pius XII in articles which appeared in The Weekly Standard. Just a few years later he would find himself facing the same malcontents at work on Mel Gibson's The Passion of the Christ — among them, James Carroll and Daniel J. Goldhagen. The response from conservative Jews undoubtedly helped foil what liberals and anti-Catholic bigots considered an easy mop-up job. Among Gibson's high profile Jewish defenders were Michael Medved, Rabbi Daniel Lapin and Rabbi Aryeh Spero. No longer could the "anti-Semitism" label be applied gratuitously.

Rabbi Dalin sums it up best for all people of traditional moral and political beliefs when he urges us to recall the challenges that faced Pius XII in which the "fundamental threats to Jews came not from devoted Christians — they were the prime rescuers of Jewish lives in the Holocaust — but from anti-Catholic Nazis, atheistic Communists, and... Hitler's mufti in Jerusalem."

Matthew Anger is a freelance journalist who has written essays on history, philosophy and literature from a Catholic perspective. He lives with his wife and eight children in the Richmond, Virginia area, where he is employed as a web/multimedia designer. In addition to Seattle Catholic, he contributes to The Latin Mass and Homiletic & Pastoral Review. He also maintains Imlac's Journal, a philosophical blog.